The morning of our 5th Day allowed a glimpse of the Milano Expo 2015. This fit with our exploration of the Reggio Emilia approach to early learning because the Children’s Park at the Expo was designed to be an “atelier open to the world.” The theme of the Children’s Park, in keeping with the familiar nursery tune, was “Ring Around the Planet… Ring Around the Future.

The morning of our 5th Day allowed a glimpse of the Milano Expo 2015. This fit with our exploration of the Reggio Emilia approach to early learning because the Children’s Park at the Expo was designed to be an “atelier open to the world.” The theme of the Children’s Park, in keeping with the familiar nursery tune, was “Ring Around the Planet… Ring Around the Future.

Rolando Baldina, chief designer, along with AnnaMaria Mucchi, walked us thro ugh the process of creating the Children’s Park. It was evident that they wanted to capture the culture of a Reggio “atelier” and support the ideals of aesthetic beauty, the interconnectedness and interdependence or all things, and the critical importance of childhood. The designers succeeded in proving that there could be coherence between actions and choices; the guiding principal of the Reggio Emilia approach to interacting in the world. The park was designed around 8 premises. The park would

ugh the process of creating the Children’s Park. It was evident that they wanted to capture the culture of a Reggio “atelier” and support the ideals of aesthetic beauty, the interconnectedness and interdependence or all things, and the critical importance of childhood. The designers succeeded in proving that there could be coherence between actions and choices; the guiding principal of the Reggio Emilia approach to interacting in the world. The park was designed around 8 premises. The park would

- be accessible without an adult,

- be easy to navigate through a threaded bobbin schema,

- use technology to enhance mulit-age relationship building,

- be an active place where children could “do things,”

- allow children to create artifacts to promote identity,

- provide meeting and conversation spots,

- provide opportunities for multi-national visitors to meet and collaborate without needing translation devices or grasp of a non-native language, and

- allow real-time (Facetime or SKYPE) connections with children in other places.

A brief survey of these child-friendly, Reggio inspired exhibits follows.

Exhibit #1 – Ring Around Noses

This exhibit presents a mushroom like enclosure where a nebulizer pushed a fragrance (herb or perfume) into the air under the dome. The mushroom caps move up and down to accommodate taller or smaller children. The more children who congregate under the cap, the stronger the fragrance becomes. Thus the idea of the importance of collaboration is enhanced by this activity. Exhibits of real plants and herbs adds the appropriate visual to the olfactory encounter.

This exhibit presents a mushroom like enclosure where a nebulizer pushed a fragrance (herb or perfume) into the air under the dome. The mushroom caps move up and down to accommodate taller or smaller children. The more children who congregate under the cap, the stronger the fragrance becomes. Thus the idea of the importance of collaboration is enhanced by this activity. Exhibits of real plants and herbs adds the appropriate visual to the olfactory encounter.

Exhibit #2 – Ring Around Water

Using a funnel, children gather drops of water from tubes in the ceiling and deposit them into a collection tray. Drops that are not collected fall to the absorbent flooring and are channeled away and into the collection tray. The amount of water produced is dependent on the number of children moving under the tubes in the exhibit. Again, collaboration is key. This exhibit demonstrates the supreme importance of the water cycle; Water Is Life!

Using a funnel, children gather drops of water from tubes in the ceiling and deposit them into a collection tray. Drops that are not collected fall to the absorbent flooring and are channeled away and into the collection tray. The amount of water produced is dependent on the number of children moving under the tubes in the exhibit. Again, collaboration is key. This exhibit demonstrates the supreme importance of the water cycle; Water Is Life!

Exhibit #3 – Ring Around Life

The message of this exhibit is that all living organisms are interconnected. Visitors stand on a scale large enough to accommodate many children. The total weight is projected onto a screen converted into other animal weights. For example, the total weight of several children might be that of a billion bees or an elephant’s foot. This exhibit provides a bridge to stories about natural cycles (e.g. water, plant, rock, wheat) and demonstrates how interdependent we are on the uninterrupted continuation of these life-giving cycles.

The message of this exhibit is that all living organisms are interconnected. Visitors stand on a scale large enough to accommodate many children. The total weight is projected onto a screen converted into other animal weights. For example, the total weight of several children might be that of a billion bees or an elephant’s foot. This exhibit provides a bridge to stories about natural cycles (e.g. water, plant, rock, wheat) and demonstrates how interdependent we are on the uninterrupted continuation of these life-giving cycles.

Exhibit #4 – Ring Around Rings

This mid- stop in the progression through the Children’s Park provides an events space and open amphitheater. The stage backdrop is a series of distorting mirrors that reflect the surrounding landscape. Videos from UNICEF and the United Nations plan at routine intervals. But the space is also available for impromptu presentations by park visitors.

stop in the progression through the Children’s Park provides an events space and open amphitheater. The stage backdrop is a series of distorting mirrors that reflect the surrounding landscape. Videos from UNICEF and the United Nations plan at routine intervals. But the space is also available for impromptu presentations by park visitors.

Exhibit #5 – Ring Around Trees

Similar to shadow screens at many children’s parks and science museums, this exhibit invites children to pose while movement sensors capture a silhouette of the each child. Unique to this exhibit, however, is software that immediately begins to grow branches, leaves, and roots from the child’s shadow image changing her into a tree!

Exhibit #6 – Ring Around Energy

Again using collaboration as a model of dynamism, this exhibit invites all children, including those ‘special rights’ children with physical challenges, to hop onto a peddling device (e.g. bicycle, scooter, tricycle) and to become a member of a “pedal orchestra.” Each device is capable of producing a particular harmonizing tone, and rhythmic pulse that, when played in unison, becomes an orchestral soundscape. Peddling speed controls the volume of the music, and the addition of a single device has the capacity to completely change the audio output. Peddling also produces jets of water. Thus, the height of the fountain is likewise controlled by the number of people contributing to the activity.

Again using collaboration as a model of dynamism, this exhibit invites all children, including those ‘special rights’ children with physical challenges, to hop onto a peddling device (e.g. bicycle, scooter, tricycle) and to become a member of a “pedal orchestra.” Each device is capable of producing a particular harmonizing tone, and rhythmic pulse that, when played in unison, becomes an orchestral soundscape. Peddling speed controls the volume of the music, and the addition of a single device has the capacity to completely change the audio output. Peddling also produces jets of water. Thus, the height of the fountain is likewise controlled by the number of people contributing to the activity.

Exhibit #7 – Ring Around the Future

This exhibit harkens back to the days of the fishing pond at the county fair. Hand written messages of planetary concern and hope are enclosed inside clear plastic spheres. These bob about on the pond until another child “fishes” it out., reads it, and composes a message of her own. These are tossed back into the pond and refloated so others can fish out and read the new message. Interestingly, the first messages to begin this cycle of interconnected correspondence were composed by Reggio Emilia pre-school children. Messages now originate from many countries around the world.

This exhibit harkens back to the days of the fishing pond at the county fair. Hand written messages of planetary concern and hope are enclosed inside clear plastic spheres. These bob about on the pond until another child “fishes” it out., reads it, and composes a message of her own. These are tossed back into the pond and refloated so others can fish out and read the new message. Interestingly, the first messages to begin this cycle of interconnected correspondence were composed by Reggio Emilia pre-school children. Messages now originate from many countries around the world.

Exhibit #8 – Ring Around Play

The final stop in this journey around Children’s Park is a non-traditional playground. Capturing the value of agriculture, nutrition and the healthy body movement, designers constructed oversized vegetables and fruits as play equipment. Climbing, tag, and hide and seek are universal games played by the multi-national visitors to this Children’s Park.

The final stop in this journey around Children’s Park is a non-traditional playground. Capturing the value of agriculture, nutrition and the healthy body movement, designers constructed oversized vegetables and fruits as play equipment. Climbing, tag, and hide and seek are universal games played by the multi-national visitors to this Children’s Park.

Milano Expo 2015, with the help of Reggio kids, has made a brilliant choice in showcasing the importance of early learning in fostering a mindful, peaceful, and abundant planet.

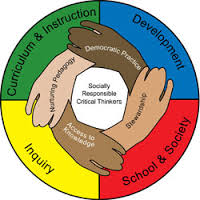

I am engaged part-time at a small, independent, Reggio-inspired Episcopal school in the heart of Silicon Valley serving children in preschool through fifth grade. Our mission states, in part, [we] ‘value innovation and tradition.’ And in our quest to educate the ‘whole child, we inspire children to have an inquiring mind and discerning heart, the courage to will and to persevere, and the gift of joy and wonder in the ever-changing world.’ (c.2010)

I am engaged part-time at a small, independent, Reggio-inspired Episcopal school in the heart of Silicon Valley serving children in preschool through fifth grade. Our mission states, in part, [we] ‘value innovation and tradition.’ And in our quest to educate the ‘whole child, we inspire children to have an inquiring mind and discerning heart, the courage to will and to persevere, and the gift of joy and wonder in the ever-changing world.’ (c.2010)

Subjects are NOT knowledge. Children’s interactions with the subject matter – the epistemological approach – IS education. Therefore investigation into Big/Essential Questions, Design Thinking, and 21st Century skill development – all parts of our curriculum delivery methodology at our small school in Los Altos, California – are allowing us to glimpse that ‘holy grail’ of education: continuity and a pluralist way of knowing.

Subjects are NOT knowledge. Children’s interactions with the subject matter – the epistemological approach – IS education. Therefore investigation into Big/Essential Questions, Design Thinking, and 21st Century skill development – all parts of our curriculum delivery methodology at our small school in Los Altos, California – are allowing us to glimpse that ‘holy grail’ of education: continuity and a pluralist way of knowing.

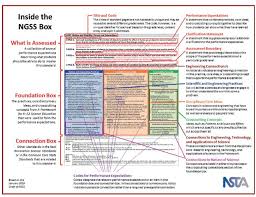

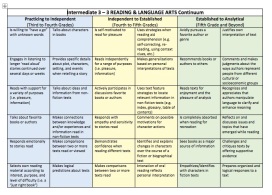

anna Cagliari was the concept of “CONTINUITY.” Why, Claudia admonished us, is continuity so important to education? Why is continuity of curriculum and its delivery methodology used as an issue to segregate different levels of schooling? By embracing the false concept of continuous growth and development at a routine or regular pace, an unrealistic expectation that children at one level will be perfectly prepared to enter the next is created. Continuity, our hosts suggested, is antithetical to child development theory and the ‘Reggio Approach.’ Continuity then, is certainly an indictment of America’s one-size-fits all Common Core.

anna Cagliari was the concept of “CONTINUITY.” Why, Claudia admonished us, is continuity so important to education? Why is continuity of curriculum and its delivery methodology used as an issue to segregate different levels of schooling? By embracing the false concept of continuous growth and development at a routine or regular pace, an unrealistic expectation that children at one level will be perfectly prepared to enter the next is created. Continuity, our hosts suggested, is antithetical to child development theory and the ‘Reggio Approach.’ Continuity then, is certainly an indictment of America’s one-size-fits all Common Core.

A 15 minute black and white film loop of a choppy ocean. A variety of black, white, and transparent objects (e.g. styrofoam pillars, various geometric shapes) are provided. By arranging these objects in front of the light source (a ceiling mounted projector) students are invited to “play” with the ocean scene. A flat bed sheet suspended from the ceiling on a dowel acts as a screen.

A 15 minute black and white film loop of a choppy ocean. A variety of black, white, and transparent objects (e.g. styrofoam pillars, various geometric shapes) are provided. By arranging these objects in front of the light source (a ceiling mounted projector) students are invited to “play” with the ocean scene. A flat bed sheet suspended from the ceiling on a dowel acts as a screen.

her video loop of a full-color underwater scene delineated another section of the “Digital Landscapes” atelier. This area invited children to set up typical 3-D objects to transform the scene. But mirrors were added to this area so children could play with reflected and repeated images to make patterns.

her video loop of a full-color underwater scene delineated another section of the “Digital Landscapes” atelier. This area invited children to set up typical 3-D objects to transform the scene. But mirrors were added to this area so children could play with reflected and repeated images to make patterns.

The entire afternoon was to be a “hands-on” exploration of the five “atelier” spaces at the Loris Malaguzzi Center. Lorella Trancossi introduced the concept of the Reggio “atelier,” and shared how each individual “atelier,” or workshop space, was related to each of the others. The unifying concept of the atelier space is that each large, open area provides unlimited possibilities for exploration leading to the transformation of thoughts and transmission of ideas. [Please note that we were not permitted to take photographs of the atelier spaces. The images in this post are representative samples gathered from the Internet.]

The entire afternoon was to be a “hands-on” exploration of the five “atelier” spaces at the Loris Malaguzzi Center. Lorella Trancossi introduced the concept of the Reggio “atelier,” and shared how each individual “atelier,” or workshop space, was related to each of the others. The unifying concept of the atelier space is that each large, open area provides unlimited possibilities for exploration leading to the transformation of thoughts and transmission of ideas. [Please note that we were not permitted to take photographs of the atelier spaces. The images in this post are representative samples gathered from the Internet.]

connection between digital devices and their capacity to project light and manipulative materials (e.g. blocks, statues, plexiglass shapes). Mixing these materials provokes hypotheses around science co

connection between digital devices and their capacity to project light and manipulative materials (e.g. blocks, statues, plexiglass shapes). Mixing these materials provokes hypotheses around science co ncepts (i.e. physics and the properties of light, balance and stability, etc.) allowing even preschoolers to engage in the language of learning. I was gratified to see how imaginatively the “atelieristas” – persons who set up and facilitated users in the space – recycled decades old technologies like overhead projectors.

ncepts (i.e. physics and the properties of light, balance and stability, etc.) allowing even preschoolers to engage in the language of learning. I was gratified to see how imaginatively the “atelieristas” – persons who set up and facilitated users in the space – recycled decades old technologies like overhead projectors. Transforming raw

Transforming raw

ages, the fifth “atelier,” is showcased in the

ages, the fifth “atelier,” is showcased in the  The morning of our 5th Day allowed a glimpse of the Milano Expo 2015. This fit with our exploration of the Reggio Emilia approach to early learning because the Children’s Park at the Expo was designed to be an “atelier open to the world.” The theme of the Children’s Park, in keeping with the familiar nursery tune, was “Ring Around the Planet… Ring Around the Future.

The morning of our 5th Day allowed a glimpse of the Milano Expo 2015. This fit with our exploration of the Reggio Emilia approach to early learning because the Children’s Park at the Expo was designed to be an “atelier open to the world.” The theme of the Children’s Park, in keeping with the familiar nursery tune, was “Ring Around the Planet… Ring Around the Future. ugh the process of creating the Children’s Park. It was evident that they wanted to capture the culture of a Reggio “atelier” and support the ideals of aesthetic beauty, the interconnectedness and interdependence or all things, and the critical importance of childhood. The designers succeeded in proving that there could be coherence between actions and choices; the guiding principal of the Reggio Emilia approach to interacting in the world. The park was designed around 8 premises. The park would

ugh the process of creating the Children’s Park. It was evident that they wanted to capture the culture of a Reggio “atelier” and support the ideals of aesthetic beauty, the interconnectedness and interdependence or all things, and the critical importance of childhood. The designers succeeded in proving that there could be coherence between actions and choices; the guiding principal of the Reggio Emilia approach to interacting in the world. The park was designed around 8 premises. The park would

stop in the progression through the Children’s Park provides an events space and open amphitheater. The stage backdrop is a series of distorting mirrors that reflect the surrounding landscape. Videos from UNICEF and the United Nations plan at routine intervals. But the space is also available for impromptu presentations by park visitors.

stop in the progression through the Children’s Park provides an events space and open amphitheater. The stage backdrop is a series of distorting mirrors that reflect the surrounding landscape. Videos from UNICEF and the United Nations plan at routine intervals. But the space is also available for impromptu presentations by park visitors.

es believe, the Reggio teacher begins with the child as “all knowing.” It is (not simply) up to the astute and sharp-witted teacher to listen, to understand what the child already knows, and to set the provocation for constructing further learning. In a nutshell, the teacher’s role is active and thoughtful engagement in observation, interpretation, and documentation. Teachers expend much physical and mental energy learning how each unique child responds to concepts or ideas, both individually and as a member of a group. The teacher’s role, then, is reflexive and self-reflective. It is that of a researcher and a ‘chooser’ of follow-on provocations. It involves quiet mindfulness away from children, collaboration with mentors or colleagues, or reviewing a video of the encounter just completed.

es believe, the Reggio teacher begins with the child as “all knowing.” It is (not simply) up to the astute and sharp-witted teacher to listen, to understand what the child already knows, and to set the provocation for constructing further learning. In a nutshell, the teacher’s role is active and thoughtful engagement in observation, interpretation, and documentation. Teachers expend much physical and mental energy learning how each unique child responds to concepts or ideas, both individually and as a member of a group. The teacher’s role, then, is reflexive and self-reflective. It is that of a researcher and a ‘chooser’ of follow-on provocations. It involves quiet mindfulness away from children, collaboration with mentors or colleagues, or reviewing a video of the encounter just completed.

on can be recorded and artistically presented to the public as an informational display. The use of photography to capture just the right moment was always in evidence. Binders full of other examples of documentation I perused consisted of T-charts where hastily written pencil transcripts of student conversation were added on the left, and teacher interpretation of student understanding was written to the right. Interestingly, the teachers show their thinking/interpretation by using a highlighter to focus on particular statements or words uttered by the children. Then, by stringing together these phrases, the teacher was able to interpret where to take the learning and determine what extensions of the original concept she might plan for the following day. What materials would she make available? What might her provocative questions be? One day’s documentation becomes the next day’s lesson plan. You see, of course, how natural and fluid learning becomes. Shouldn’t all learning be as compelling?

on can be recorded and artistically presented to the public as an informational display. The use of photography to capture just the right moment was always in evidence. Binders full of other examples of documentation I perused consisted of T-charts where hastily written pencil transcripts of student conversation were added on the left, and teacher interpretation of student understanding was written to the right. Interestingly, the teachers show their thinking/interpretation by using a highlighter to focus on particular statements or words uttered by the children. Then, by stringing together these phrases, the teacher was able to interpret where to take the learning and determine what extensions of the original concept she might plan for the following day. What materials would she make available? What might her provocative questions be? One day’s documentation becomes the next day’s lesson plan. You see, of course, how natural and fluid learning becomes. Shouldn’t all learning be as compelling?

ulum is a fundamental belief that all children are capable. Concepts develop over time and in a spiral pattern as each idea is met with new cognition as the child grows older. A huge piece of this curriculum development approach is the teacher’s focus on “process” and making student/child thinking visible. Recording “how children know.” This is accomplished through grouping strategies, collegial meeting protocols, presentations, exhibits, and documentation.

ulum is a fundamental belief that all children are capable. Concepts develop over time and in a spiral pattern as each idea is met with new cognition as the child grows older. A huge piece of this curriculum development approach is the teacher’s focus on “process” and making student/child thinking visible. Recording “how children know.” This is accomplished through grouping strategies, collegial meeting protocols, presentations, exhibits, and documentation.

1980 the ‘Reggio Approach’ to early childhood education – where all learning springs directly from children’s interests, questions, and ideas – had become a global phenomenon. The responsibility of the municipality to continue to build the concrete conditions that protect the rights of children had become a sustainable value in the Reggio Emilia community. And, even through hard times of unemployment and declining population, the city continues to put its money where its values lie. This altruism, this fidelity to the future, was my biggest take-away from the entire tour experience. And, it begs this question: Why can’t the richest country on the planet provide similar educational foundation to its youngest citizens?

1980 the ‘Reggio Approach’ to early childhood education – where all learning springs directly from children’s interests, questions, and ideas – had become a global phenomenon. The responsibility of the municipality to continue to build the concrete conditions that protect the rights of children had become a sustainable value in the Reggio Emilia community. And, even through hard times of unemployment and declining population, the city continues to put its money where its values lie. This altruism, this fidelity to the future, was my biggest take-away from the entire tour experience. And, it begs this question: Why can’t the richest country on the planet provide similar educational foundation to its youngest citizens?